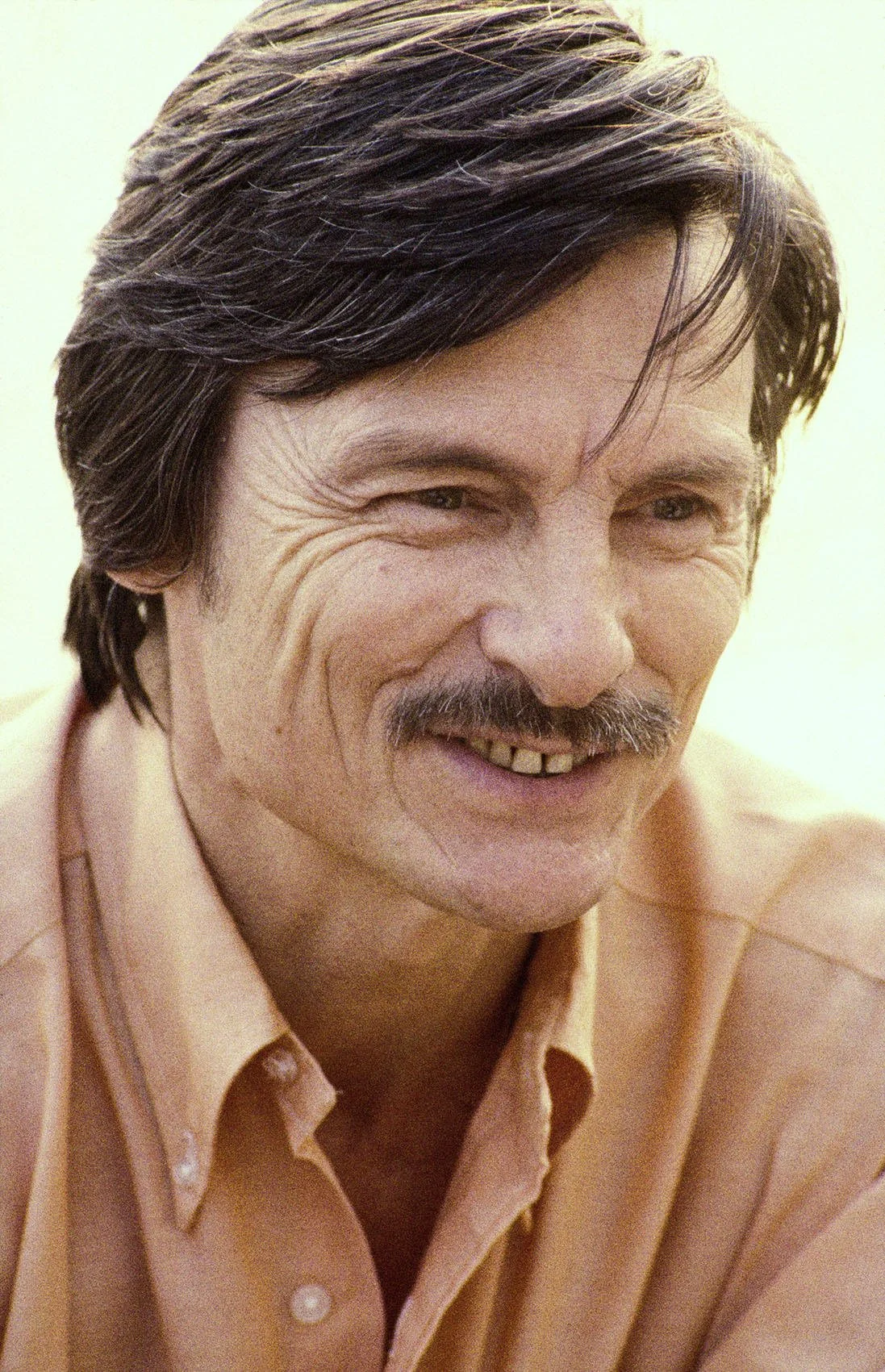

David Gothard is a pioneering artistic director, theatre-maker and producer whose influence has spanned multiple generations from around the globe. And he’s funny as hell.

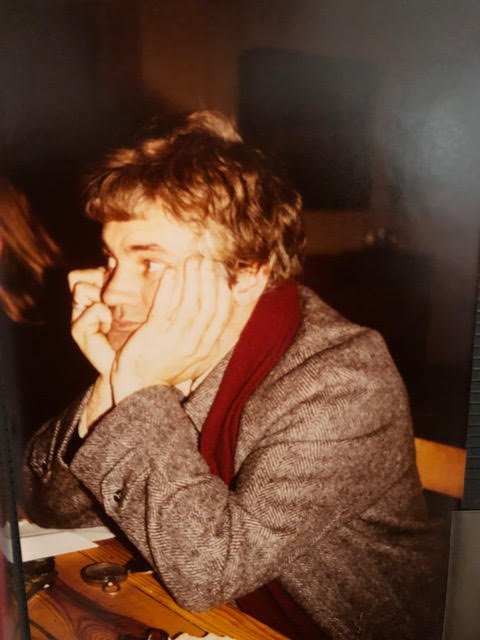

photo: Carmen Alt-Chaplin

Budapest, 1972

THE DAVID GOTHARD ARCHIVES

The David Gothard Archive contains materials, writings, letters, statements, manifestos, books, artworks, photos, sound and video recordings that David Gothard has been collecting while developing direct collaborations with artists such as Tadevz Kantor, Michael Clark, Randy Warshaw, Hanif Kureishi, Italo Calvino, Laurie Anderson and many more.

The archive is mainly focused on visual arts and performance from the early eighties and include Dario Fo’, Bread and Puppet, Squat, Le Cirque Imaginaire, and Samuel Beckett, to name a few.

Based between London (UK) and Gorizia (Italy) The David Gothard Archive is curated by Michele Drascek and has been collected and researched since 2010.

For information on the archive please contact micheledrascek@gmail.com

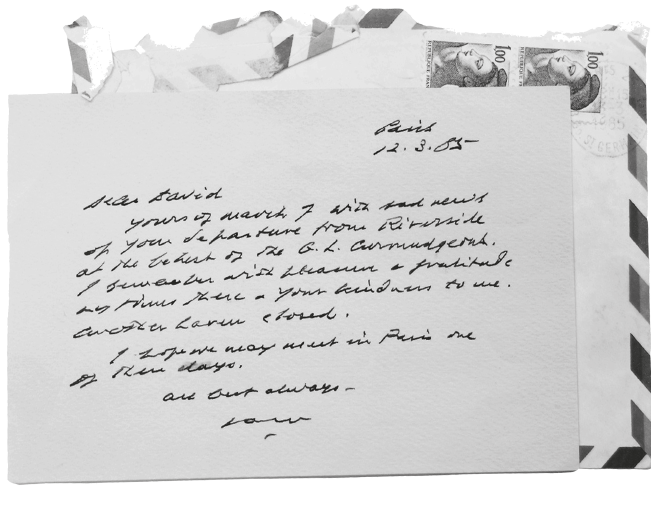

One of many postcards sent by Samuel Beckett in Paris to David Gothard in London. This one reads

Dear David,

Yours of March 7 with sad news of your departure from Riverside at the Behest of the G.L Curmudgeons. I remember with warmth and gratitude my time there and your kindness to me. Another haven closed. I hope we may meet in Paris one of these days. All best always, Sam.

BECKETT AT RIVERSIDE

In 1980 Samuel Beckett and the San Quentin Drama Workshop took up residence for two weeks at Riverside Studios in Hammersmith, London. Although never intended for an English audience, they had come to rehearse their production of Beckett’s Endgame, which was to be performed at the Abbey Theatre, Ireland.

Riverside Studios during the eighties was a hub of activity under the artistic directorship of David Gothard. Cirque Imaginaire, Ekkehard Schall of the Berliner Ensemble, and Miro’s first theatre collaboration since Diagilev, Merma Never Dies, were amongst the many introductions to Britain made at the Riverside. As well as being home to the Motley Design Course, there was a strong community of resident artists, including Bruce Mclean and the architect Will Alsop. Young writers such as Hanif Kureishi were developed, and Tarkovsky, who had come to England from Italy after exiting Russia, found a home there whilst preparing for his film The Sacrifice.

The rehearsals went well, and four years later in 1984, the San Quentin Drama Workshop, Walter Asmus and Beckett returned for rehearsals of Beckett’s seminal play Waiting for Godot, directed by Samuel Beckett.

Again, this production was never intended for UK audiences, instead leaving for the Adelaide Festival in Australia. However, due to the creative hospitality of David Gothard many people were involved in these two events including artists, journalists, and school children, all benefiting from the particular atmosphere of work concentration and creativity generated by the rehearsal process.

AN EXCERPT FROM HANIF KUREISHI’S INTRODUCTION TO MY BEAUTIFUL LAUNDRETTE

When I finished a draft of My Beautiful Laundrette, and Mother Courage had gone into rehearsal, Karin Bamborough, David Rose and I discussed directors for the film.

A couple of days later I went to see a friend, David Gothard, who was then running Riverside Studios. I often went for a walk by the river in the early evening, and then I’d sit in David’s office. He always had the new books and the latest magazines; and whoever was appearing at Riverside would be around. Riverside stood for tolerance, scepticism and intelligence. The feeling there was that works of art, plays, books and so on, were important. This is a rare thing in England. For many writers, actors, dancers and artists, Riverside was what a university should be: a place to learn and talk and work and meet your contemporaries. There was no other place like it in London and David Gothard was the great encourager, getting work on and introducing people to one another.

He suggested I ask Stephen Frears to direct the film. I thought this an excellent idea, except that I admired Frears too much to have the nerve to ring him. David Gothard did this and I cycled to Stephen’s house in Notting Hill, where he lived in a street known as ‘director’s row’ because of the number of film directors living there.

FORGOTTEN MAN

Written and Directed by Arran Shearing

Executive Produced by David Gothard

David Served as Executive Producer on the multiple award-winning feature film Forgotten Man, which stars Obi Abili, Jerry Hall, Eleanor McLoughlin, and Errol McGlashan.

Forgotten Man premiered at Cinequest in 2017 and went on to screen at over twenty festivals worldwide, winning multiple awards, including Best Film at the Sydney Independent Film Festival, Best Performance at the New York Independent Film Festival and the Leo Award for Cinematography, among others.

Forgotten Man tells the story of a young actor in an East London theatre company for the homeless who romances a wealthy out-of-towner in the bustling streets of contemporary London.

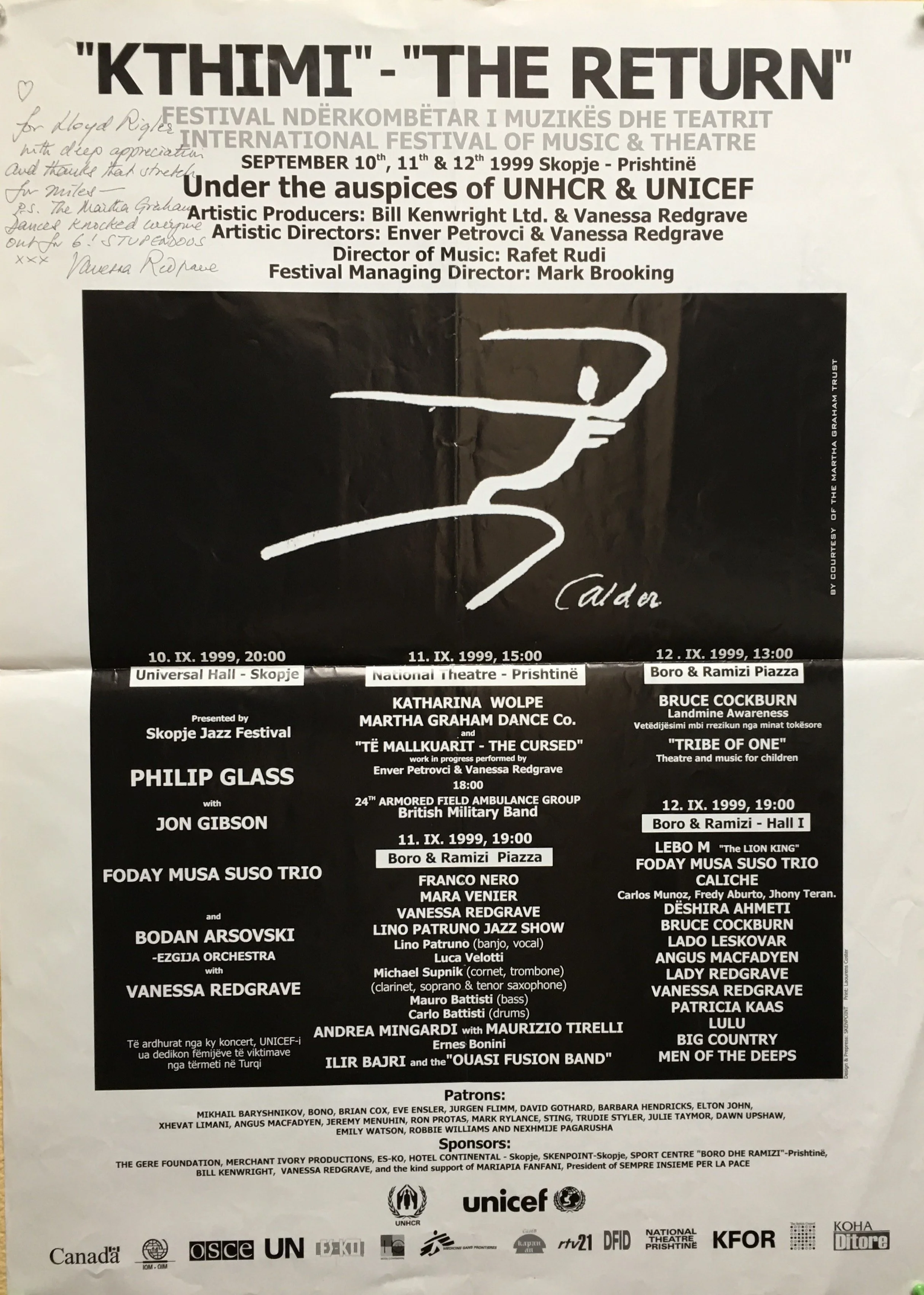

Poster for the return festival, 1999 with note from Vanessa Redgrave

“KTHIMI” THE RETURN

Prior to directing Hamlet as the first theatrical production in Kosovo following the ethnic war, Gothard produced ‘The Return’ festival along with Vanessa Redgrave. Patrons included Brian Cox, Elton John, Bono, Sting, Trudie Styler, and Mark Rylance.

The festival was held in Prishtine in 1999 and was a celebration of the return of the scores of displaced Kosovans to their nation-state. The festival also served as a thank you to neighboring Macedonia for hosting the refugee camps during the war.

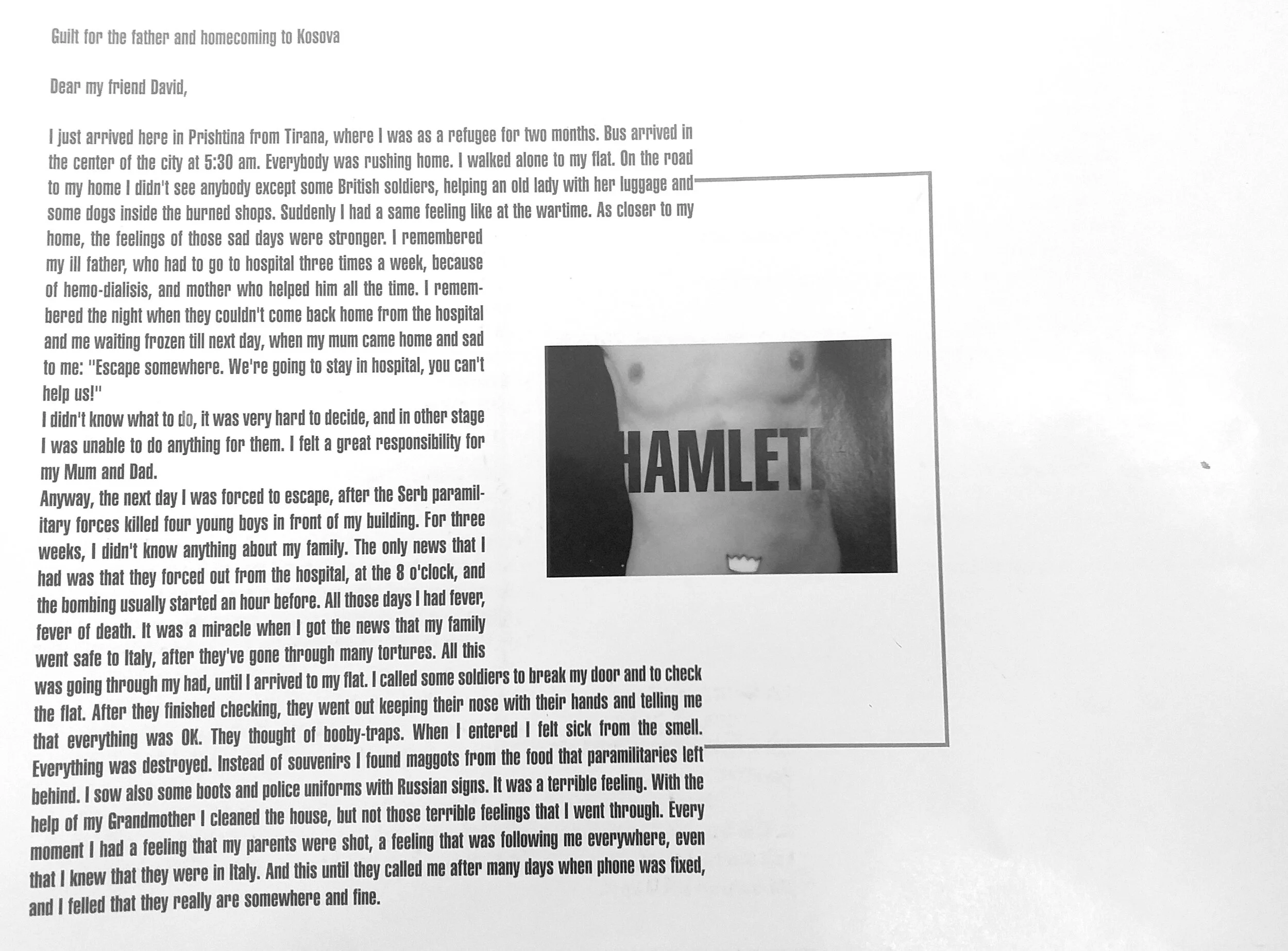

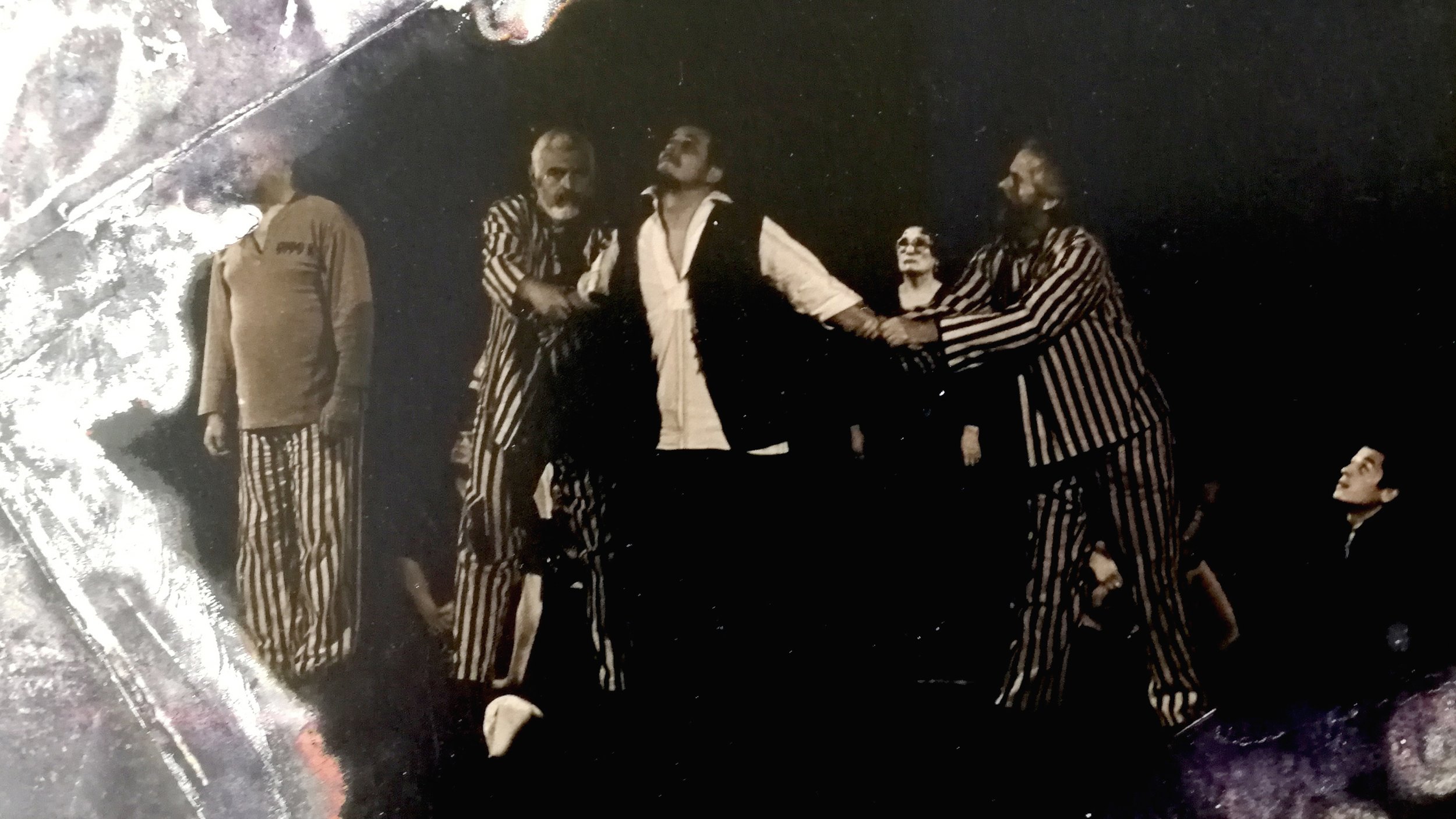

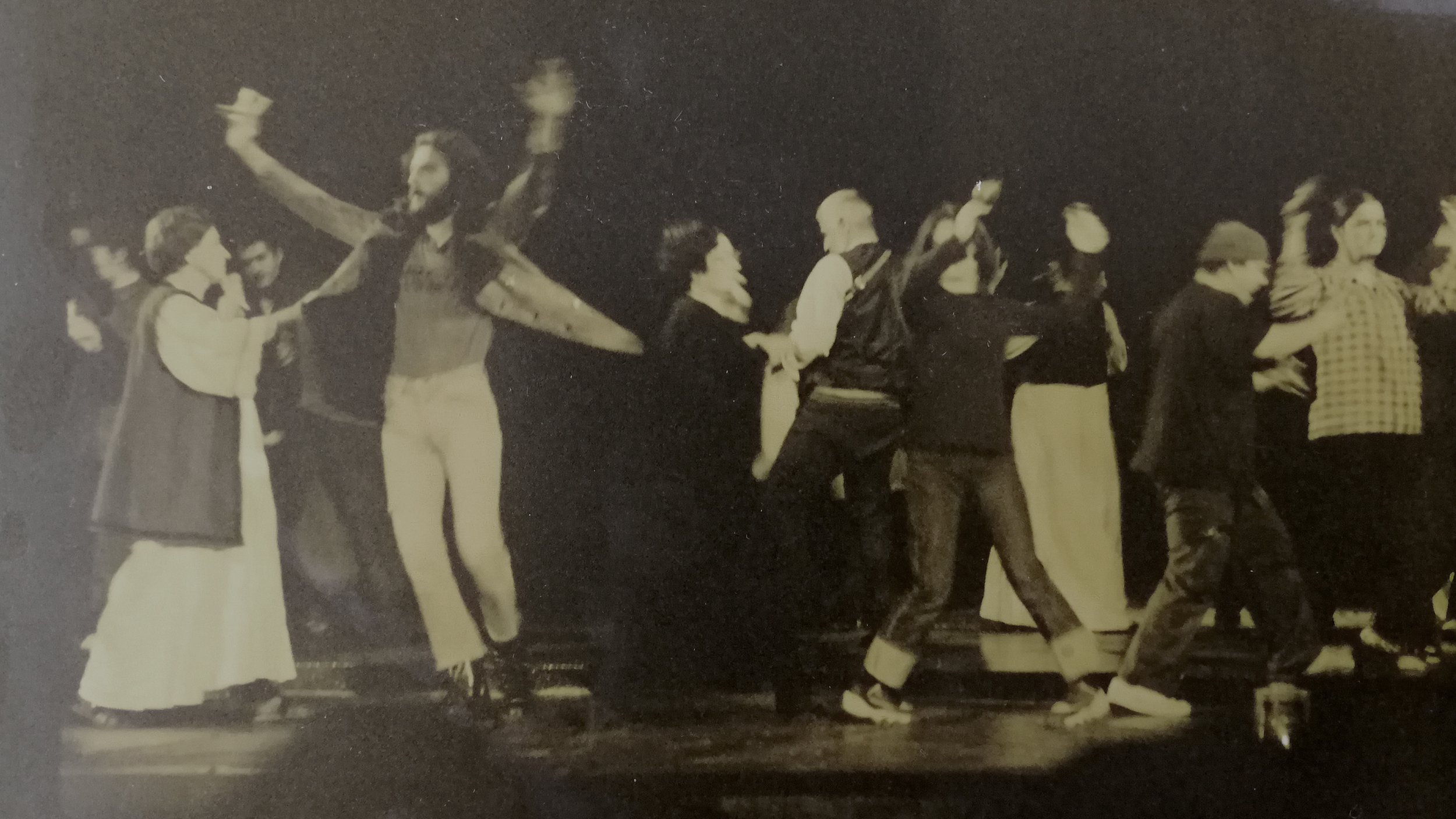

HAMLET

DIRECTED BY DAVID GOTHARD PRISHTINA, 1999

Hamlet played by Armond Marina.

Designer: Edmond Agagjyshi

Photography: Edib Agagjyshi

With funding from the British Government, David Gothard selected Hamlet as the first theatrical production in Prishtina since the ethnic war between Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo, which was halted by the arrival of NATO troops in mid-June.

"Everybody has a 'to be or not to be' story in Pristina," Gothard said. "This is the pleasure of doing the play here. They understand it all. Should they stay or go? Should they fight or not? Did they have to look after somebody else or take care of themselves?”

Gothard stitched two groups of actors into a single, 70-person company: those ethnic Albanian actors who fled after a wave of government repression hit Kosovo in 1989, and a younger, more adventurous group that operated a half-underground theatre here until the war forced them to leave or hide.

The National Theatre, where the play opened to a packed house, lacked electricity or heat during the day and often had to rely on a generator at night. No funds were available for props, and most of the players took the stage in tennis shoes. Still, Gothard said, "the corridors were filled with people desperate to do some work.”

The translation was by Fan S. Noli, the Harvard-educated poet and archbishop who was Albania's president during its short-lived democracy early in the century.

Hamlet toured the stricken and destroyed cities of Kosovo and opens the cultural programme of the World Aids Conference in the Opera of Durban, South Africa. A year later Gothard directed Macbeth followed by Jeton Neziraj's "The Bridge" , the first play to be done simultaneously in the Kosovan and Albanian language.

ALTITUDE

This film documents David Gothard and Joseph Fiennes in Tibet where Gothard directed Fiennes performing a solo Shakespeare program with percussionist Corinna Silvester from the National Theatre. Performances were improvised in rural communities, including Muslim China and monasteries in Tibet. Gothard and Fiennes directed the first official Shakespeare workshop at the University of Lhasa.

Andrei Tarkovsky photographed by Richard Haughton

Andrei Tarkovsky and David Gothard

Excerpt from an interview with David on Tarkovsky.

“My working with Tarkovsky was very much as a welcoming friend, not in a formal way through my work at Riverside Studios, despite there being a couple of packed public lectures by him and a season of films. After Tarkovsky decided to do his press conference in Italy explaining his position in not returning to Russia, we were introduced by Claudio Abbado, conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, a mutual friend. I hosted a committee at Riverside for campaigning for the release of his teenage son to join him from Russia. That eventually proved successful through the intervention of President Mitterand. Our second connection was to raise the financial partnership with the Swedes for the making of "The Sacrifice" which was done through the legendary head of Channel 4, Jeremy Isaacs. This then led to our beginning to work on his film project of "Hamlet". To quote Tarkovsky, "the third miracle".

Shortly after, the Greater London Council decided to withhold funding for Riverside because of its "elitism". They cited as an example, the showing of Tarkovsky films with foreign sub-titles… all clearly in the document presented with the opener: "Now for the Stalinist solution to Riverside. " It turned out to mean that there should be no discussion on further funding.”

THE TIMES, AUGUST 4, 1982

VOTING ON THE FATE OF RIVERSIDE STUDIOS

When Peter Gill and David Gothard first got their feet in the door they realized that the studios offered a unique halfway house between the fringe and the institutional. Beyond that, their only policy was to work at what they did best.

In Gill’s case that meant immaculate classical productions in the Royal Court tradition. For Gothard it meant developing his East European theatrical experience (“I went abroad instead of joining the fringe:) into an international network for London. Riverside was launched with two magnificent productions - Gill’s As You Like It and Kantor’s The Dead Class - which can be seen as the foundations of all its other work. However open it may be to experiment and untried artists, even to pot-throwers, it remains a home of exacting classical standards and the one regular London platform for world theatre.

One inescapable penalty befalling such an organism is that of being carved up by specialists. To a ballet critic, Riverside’s main claim to attention would probably be its contribution to modern dance; to cultural historians, its pathfinding explorations of Mayakovsky and Eisler. Much of its work remains invisible. But to aspiring playwrights who get a guaranteed reading from the literary manager, David Leveaux, or to the jobless local boys who are taken on as technical apprentices, that side of the operation would count for more than anything the reviewers see.

However, I do not think I am entirely theatrically blinkered in viewing the Royal Court connexion as a crucial component in this Depression success story. Gill and Gothard were both Royal Court men. Then, last year, the ageless Margaret Harris, co-founder of Motley and a close colleague of George Devine from the early 1930s to the launching of the Court in 1956, moved her Theatre Design Course into Riverside. As usual, it happened by accident with no managerial blueprint. But the result is that an unbroken tradition of 50 years’ theatre history is now housed under the same roof.

Letter from the Venetian composer, Luigi Nono, in 1984 before conducting a concert at Riverside Studios.

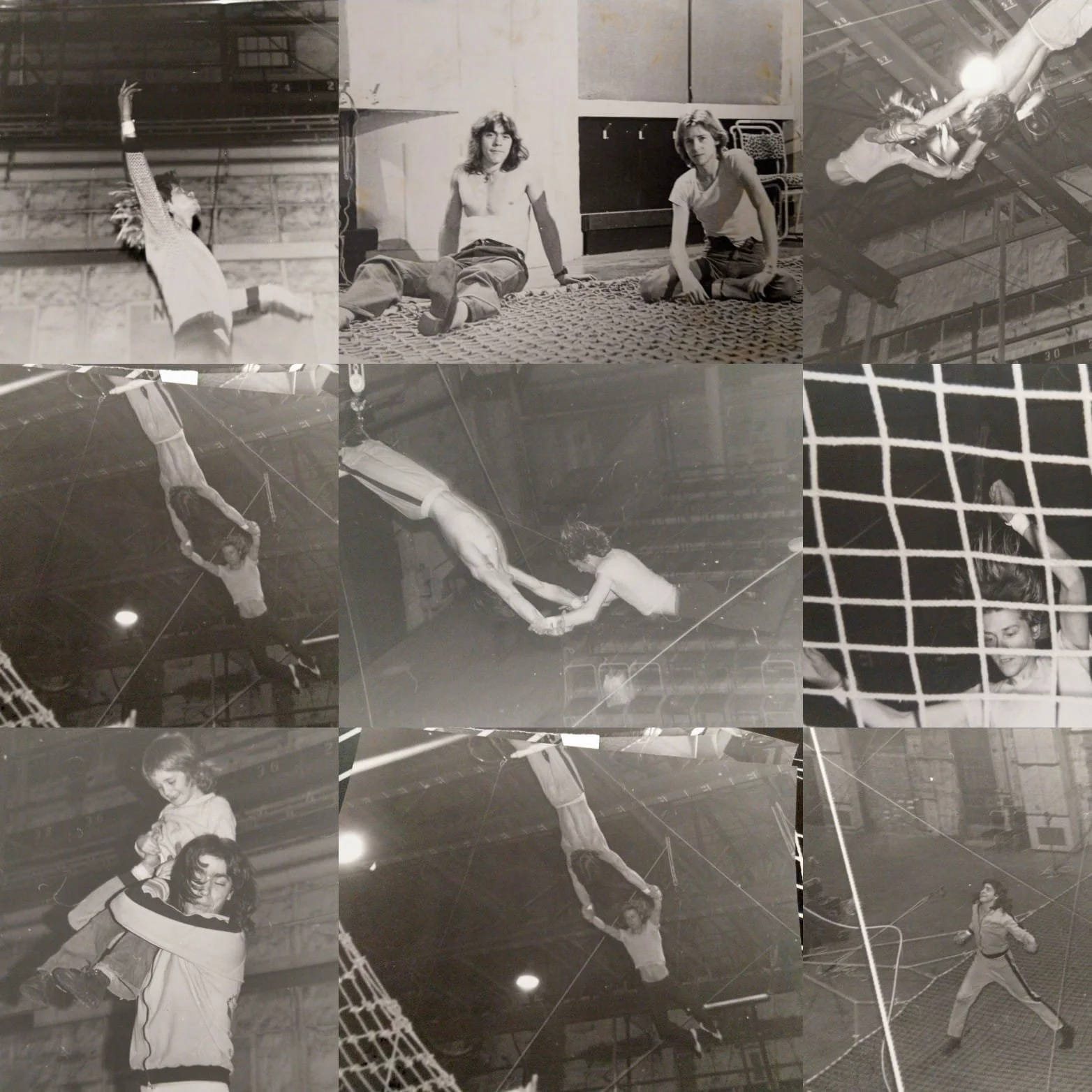

Richard Brooker, Revel Fox

This trapeze rig was built for community classes at Riverside in a studio by young South African trapezists.

Excerpt from the acknowledgments of Patrick Galbraith’s In Search of One Last Song

I will forever be indebted to the remarkable David Gothard who has been part of this book since it was just a few scribbled notes laid out across the table in a greasy pub on a rainy Tuesday afternoon. He has read every bit of In Search of One Last Song and there’s hardly a page that hasn’t been improved by his strange magic and astute criticism.

A STAY OF EXECUTION AT RIVERSIDE STUDIOS

THE RIVER Thames took on new life this week. At Shepperton, someone hooked hooked the first salmon for 150 years, and at Hammersmith, in the small hours of Thursday morning, local councillors agreed on a stay of execution for the Riverside Studios. For the artistic director, David Gothard, who has been there since the studios were started in 1978, and his myriad supporters and co-workers, it has been a debilitating time. They heaved a very tired sigh of relief.

Gothard, spare and ascetic and faintly owlish in appearance, seems to live on his nerves and glucose tablets, washed down with black coffee. The morning after the reprieve found him not quite knowing whether he was coming or going. “I’m usually cool, calm and intelligent, but I think you know why I’m like this…”

Chopping the air - and, one suspects, certain Hammersmith councillors - with emphatic gestures of his hands, and peppering his words with occasional expletives, he insists he is not a political animal, but someone who cares passionately, even recklessly, about the arts. “The joy in Britain until now,” he says “has been that certain areas, like the arts, have not been party politics. Now, the politicians have got one by the throat.”

For a heck of a lot of years, he adds, Riverside’s theatre, one of the most innovative in the country, has been playing to packed houses. Turnover has been approaching £1 million a year. “We are not chic” he says. “We are here because people like what we’re doing. We have commanded a lot of talent, sweat and loyalty, and I just want to say to the politicians: ‘For God’s sake, don’t be stupid. You’re exhausting us.’ People come, so why the hell should we apologise?…”

The reprieve is, however, a very short-term measure, and, unless further funds are forthcoming, the energy-sapping lobbying will begin all over again. Gothard is angry and frustrated at such a situation; he is wanting to bring the Imaginary Circus back for the Christmas season and wants to give the go-ahead for other shows and exhibitions. Private donations from distinguished people in the arts, even from a big bank or two, help enormously but they are not the right solutions.

Nothing daunted, Gothard is off to Poland in the next few days to see if he can bring over the Taddeusz Kantor group from Cracow at a later date.

Coincidentally, the Studios’ reprieve has come in the last week of their splendid exhibition of the graphic work of the quintessential Soviet revolutionary, Mayakovsky (which ends tomorrow). A feature of the exhibition is the telegram sent by the impresario Meyerhold to Mayakovsky in 1928, which echoes rather piquantly the message from Gothard to Hammersmith Town Hall. “For the last time” it said “I appeal to your common sense. The theatre is dying…” Mayakovsky rose to the occasion; so, in its faltering way, did Hammersmith.

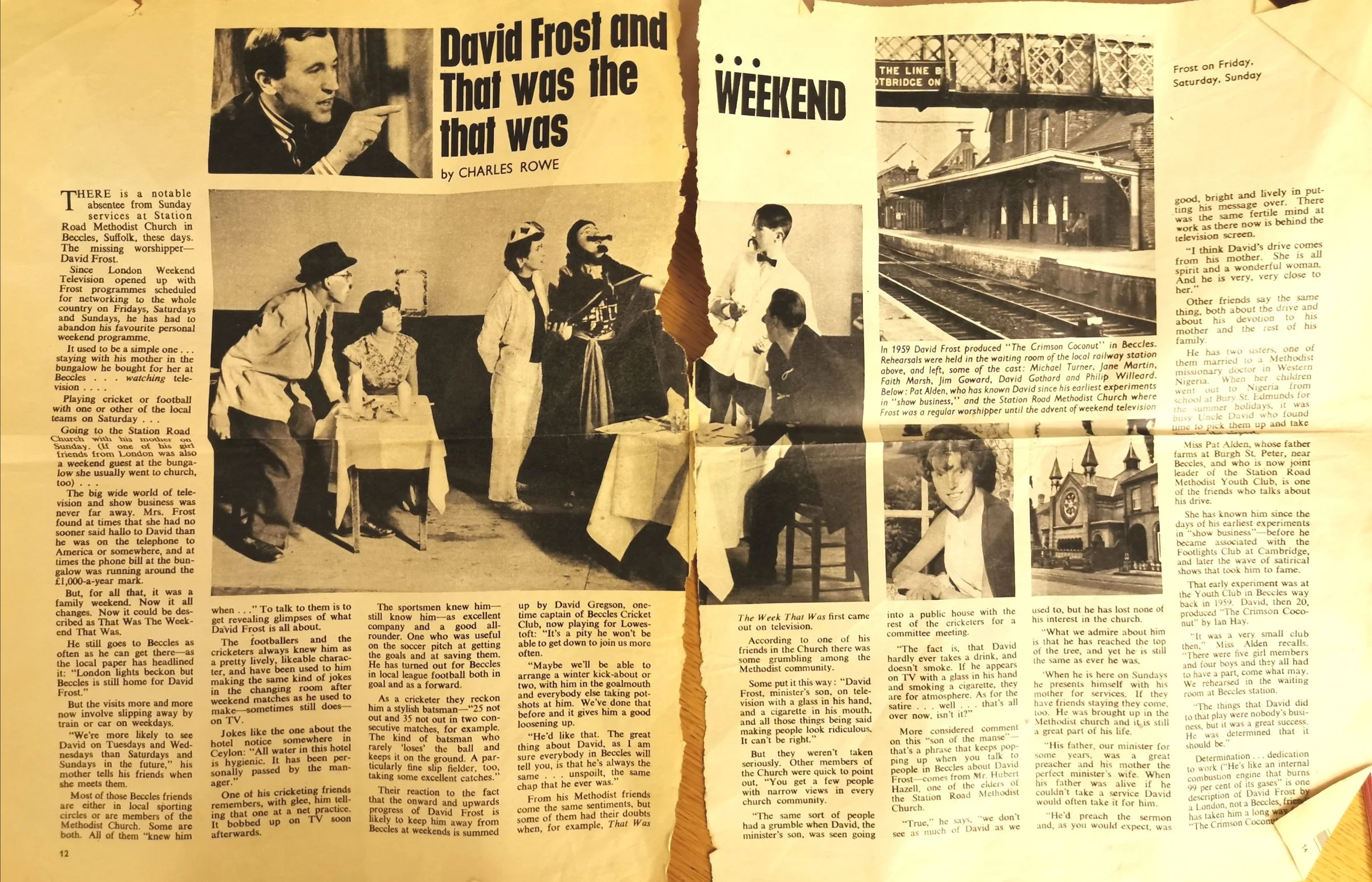

FROST/ GOTHARD

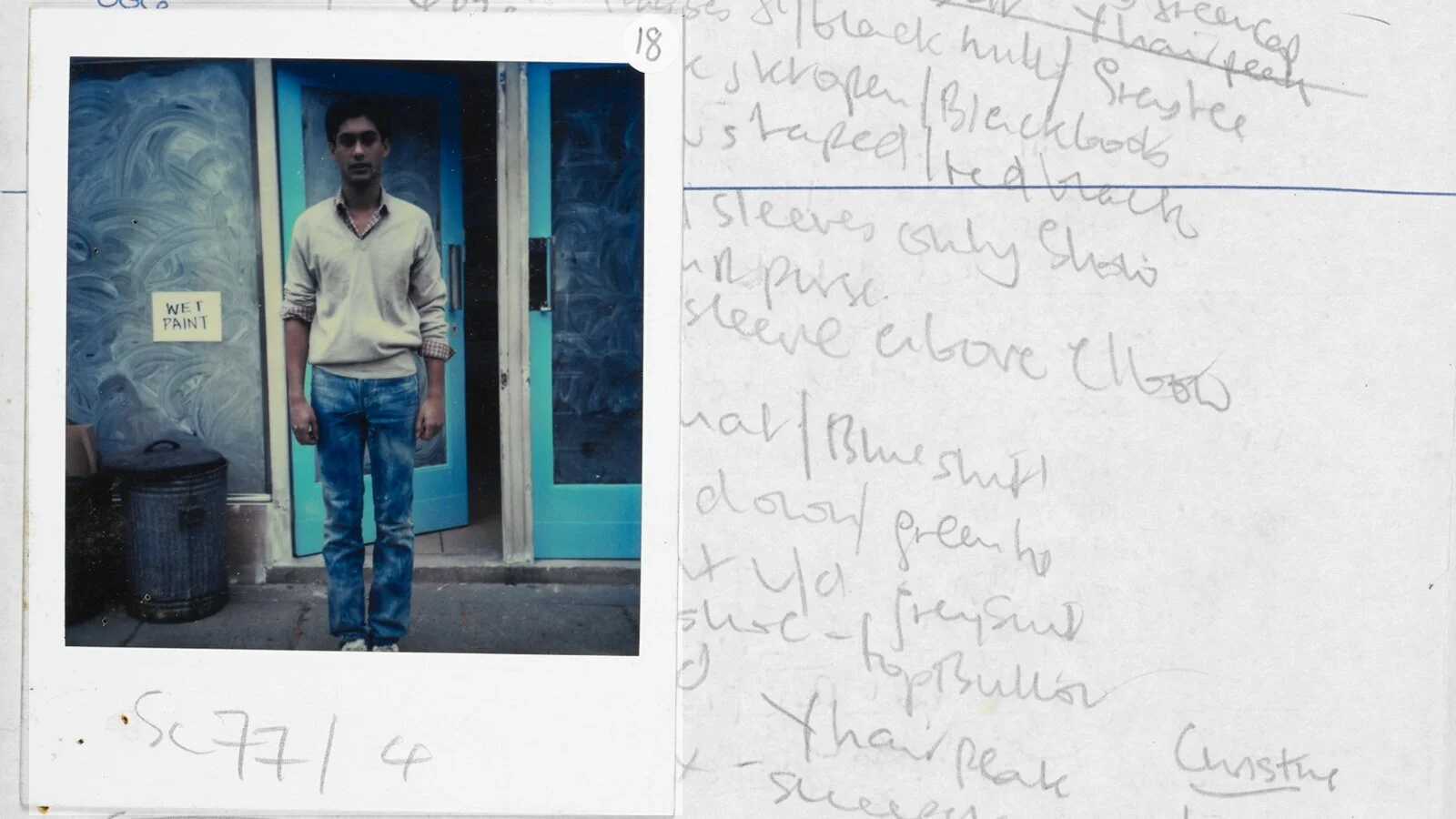

In 1959 David Frost produced “The Crimson Coconut” in Beccles. Rehearsals were held in the waiting room of the local railway station above, and left, some of the cast: Michael Turner, Jane Martin, Faith Marsh, Tim Coward, David Gothard and Philip Willeard. Below: Pat Alden, who has known David since his earliest experiments in “show business,” and the Station Road Methodist Church where Frost was a regular worshipper until the advent of weekend television.

A LIFE IN THE ARTS

interview by

Fifty years into his career in theatre, cinema and the arts, David Gothard CBE (MA Mental Philosophy 1969) reflects back on influential teachers, new ways of thinking, and bluffing his way to success.

LURED BY ITALIAN

I must have come to study in Edinburgh in 1965 for Italian Studies. Very few universities had them. By chance an itinerant retired officer came twice a week to my Suffolk state school, Sir John Leman, to teach me and one girl from the Lowestoft Covent School.

My family was from East Anglian villages on both sides: gamekeepers at Sandringham, hemp weavers on the River Waveney and above all, my grandfather was a Suffolk Punch horse man behind the plough. My father was a printer. In short we all celebrated heavy Norfolk or Suffolk dialect in all its glory. I needed the fluid and sexy release of language flying and not plodding. Italian gave me that.

Before I had completed a year in Edinburgh, I had been a translator for the Oxford expedition after the disastrous Florence floods in the late sixties and had written a paper on Dante that took me for a summer at Florence University studying literature and fine art. For a glorious month my fellow students and I entered the Uffizi Gallery at nine o’clock, one hour before the public, for our seminars. It took the whole month to get to Botticelli.

The Italian department in those days had the prestige of a great scholar, Mario Rossi, in its chair who had been at Trinity College Dublin as a close and working friend to WB Yeats, the poet, founder of the Abbey (National) Theatre, where most recently in the 21st century I have been an Associate Artist. Their expertise in Bishop Berkeley and perception never left.

PASSING INTO NEW TERRITORY

In Edinburgh all arts students had to have a pass in Moral Philosophy or Ethics under one of the great Kantian scholars still in Edinburgh, giving it a transatlantic popularity, HB Acton. It allowed me to speculate and be free mentally with a language and thinking tradition rooted in the abstract and broadest vessel of thinking possible that gave it a good grounding for our colleagues who would later graduate and transfer to New College in theology. I was liberated by this, as I rejected "playing" at student theatre for most of my university course after serious play making in my childhood. A year later, as its partner, Logic and Metaphysics, became the parallel course, I was hooked and in new territory.

I had entered a school where "the Auld Alliance" between Paris and Edinburgh through Enlightenment, David Hume to Voltaire, Adam Smith to Rousseau, were still in the air, thanks to Dr George Elder Davie whose classic, ‘The Democratic Intellect’, was illustrated every half term with a "Meal Monday" when students returned to the village to fill the sack of porridge oats as it were. I celebrated Dr Davie by writing my thesis on the father of existentialism, Edmund Husserl and his Cartesian Meditations.

I lived in a shared student flat in Ramsay Garden where Noam Chomsky was the charmer staying next door sometimes as visiting guest of the new, already celebrated Linguistics department of the University. He seemed to alternate with Paul McCartney's brother whose team from Liverpool did reviews at the Traverse Theatre Club. (Superbly it was a "club".)

TRAINEESHIPS

I am amazed at the post lifetime roots being in the early years. Between the actual graduation and a return to Edinburgh to be trainee director at the Traverse Theatre, eligible with the Scottish Arts Council because of the University background, there is a break of three years spent as a student stage manager at the Royal Court Theatre in London under the film director Lindsay Anderson and Willam Gaskill.

My first show in the Theatre Upstairs was on a Beckett triple bill designed by Jocelyn Herbert, legendary stage designer and especially Beckett's designer. A few years later this leads to my hosting Beckett at Riverside as he directed the San Quentin Prison Company a couple of times.

Riverside also incorporated the great postgraduate design school where Jocelyn had graduated from, the Motley Design Course, a link with Bauhaus and the thirties in Marcel Breuer. Production and training were hand in glove as it should be. This led to a postgraduate year in Budapest at the Bela Balasz Film Studio, shared with sociology and radicalism.

TRAVERSE TO RIVERSIDE

In the mid-seventies I received a call from the Traverse Director, the late Mike Ockrent, a Broadway legend for creating ‘The Producers and’ ‘Me and My Girl’ since. He had studied physics as my contemporary in the University:

"Do you want the good news or the bad?…The good news is that you have the Scottish Arts Council traineeship; the bad news is that you open the season in a few weeks with a one-woman play with no dialogue…Can you do it?”

I bluffed and opened the season, followed by a UK premiership of Strindberg's ‘To Damascus’. The one-woman show – the UK premiere of 'Request Programme' by Franz Xavier Kroetz, colleague of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, starring Kay Gallie – was the signal of poverty and the recession that dragged through the next decade and being a political football in the arts of community between Thatcher and her execution days with the Greater London Council.

The scene is set for UK and international work such that at the end of the year, ready for the Festival, the Scottish Arts Council and Richard Demarco sent me on a recce to report details on a new ambitious piece by Kantor in Krakow…. invited to the Festival by the Demarco Gallery. I was becoming identified with "foreign" arts. To be concise, with that Gallery I produced ‘The Dead Class’ in the Old Sculpture Court of Edinburgh College of Art where a BBC interview TV project sped it to London, where we used the former Dr Who BBC Studios and I was invited with its huge success to programme a new Arts Centre to be directed by Peter Gill. He later left to run and invent the National Theatre Studio and I become artistic director with an art gallery eventually under the Czech Milena Kalinowska, which is nominated for the Turner Prize.

My life has been in all the arts ever since, non-departmental. Scotland's great contribution was the long-term residence that I gave to Aberdonian Michael Clark as choreographer in residence, one of our greatest choreographers ever.

KOSOVO’S ARTISTIC REBIRTH

Since then I resurrected the National Theatre of Kosovo at the end of the Yugoslav Wars, with a production of ‘Hamlet’ in Albanian and took it touring to destroyed cities. We also opened the arts programme of the first World Aids Conference in Durban as guests of the Zulu nation and Muslim students. I had studied African history at Edinburgh with the great Christopher Fyfe and was paying my dues.

There had also been a festival between Macedonia and Kosovo celebrating the return of the refugees with Vanessa Redgrave, Philip Glass, Martha Graham's Company and the choir of one hundred coal miners from Nova Scotia expressing solidarity with the Kosovan miners in the lit pit hats. Lulu entertained the troops.

Film matters

There have been films on the way and I am proud that Andrei Tarkovsky, in residence at Riverside, got his full production money for ‘The Sacrifice’ as we planned what would have been his next film, ‘Hamlet’. Hanif Kureishi had been my typist as a poverty-stricken young writer who brought me a script called ‘My Beautiful Laundrette’, which we took to Stephen Frears who then persuaded his promo youngsters team to begin Working Title Films.

I am very happy that over the years I have taught, as a guest, creative writing at the University of Iowa, especially the Playwrights’ Lab. Currently, my own on or two small films give pride.

Elisabeth Welch photographed by Richard Haughton. Welch sings "Stormy Weather" in Derek Jarman's "The Tempest”.

Elisabeth Welch at Riverside

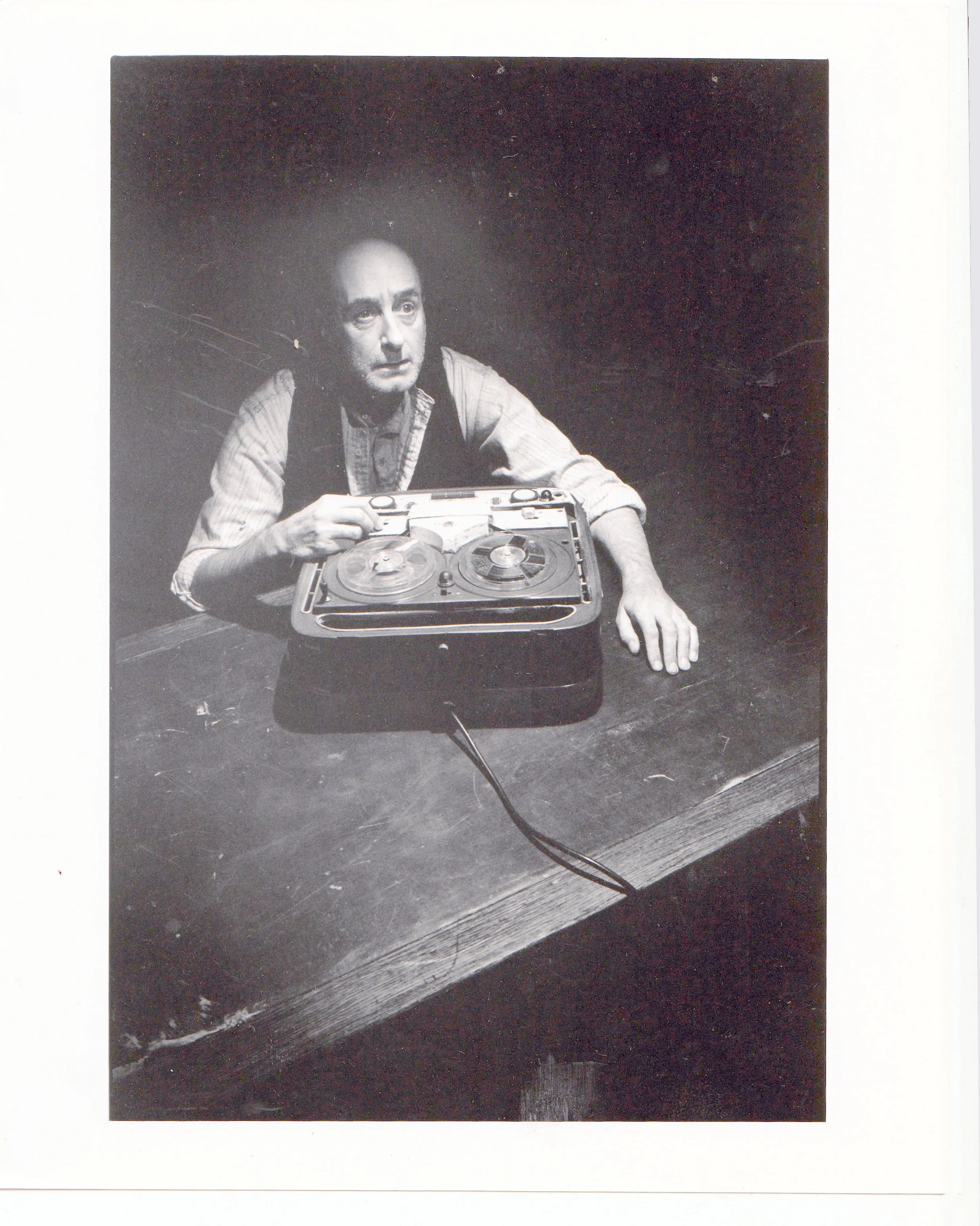

David Warrilow photographed by Stephen Vaughan

Beckett Shadow

Produced by David Gothard at Leicester, Haymarket Theatre.

Designer Jocelyn Herbert

Director Antoni Libera

GALLERY BELOW

top, from left:

Jean-Baptiste Thierree. Photographed by Michelle Haffner at Dublin Festival.

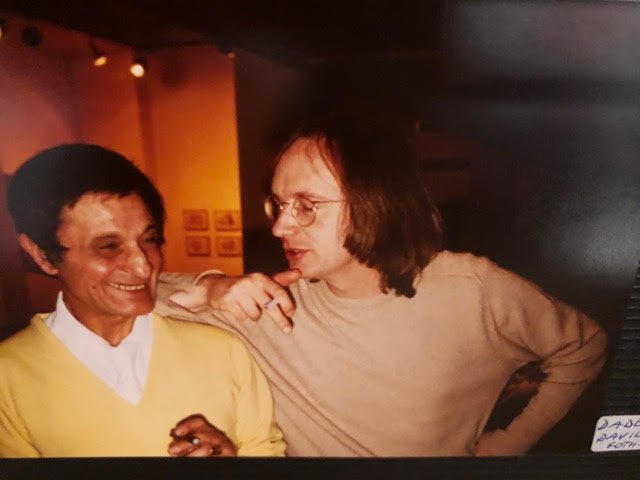

Andre Schlesser and David Gothard. Photographed by Michelle Haffner at Dublin Festival.

James ,Aurelia, and Victoria Thierree. Photographed by Michelle Haffner at Dublin Festival.

Andre Schlesser at Riverside Studios. Photographed by Michele Laird.

bottom left: tbd

bottom right: 1980, David Leveaux, then Associate Director of Riverside at the home of Matilda O'Brien in Peebles, Scotland

centre: clockwise from left:

tbd

David Gothard and Matilda O’Brien. Peebles, Scotland

David Gothard and David Leveaux, Peebles, Scotland

Andre Schlesser at Riverside Studios. Photographed by Michele Laird.

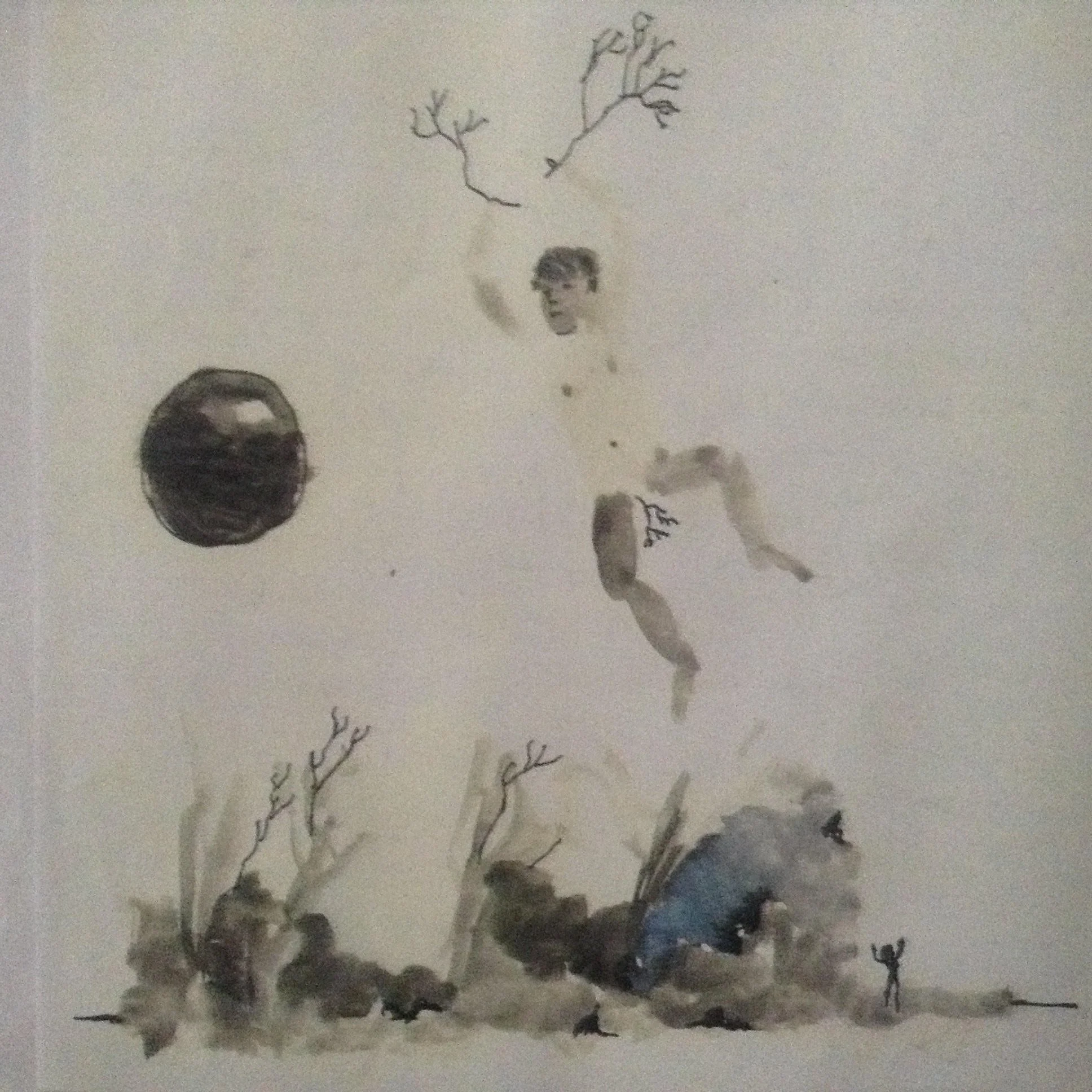

Roman Siwulak

Painting by Roman Siwulak, Cracow, Poland. Roman is an artist and member of Tadeusz Kantor's company. Kantor’s "The Dead Class" opened Riverside Studios in 1978.

Lionel Epaillard, musician with the "CIrque Imaginaire", and David Gothard in Studio One, Riverside.

Le Cirque Imaginaire

Jean-Baptiste Thierree

1964. Jean-Baptiste Thierree in Peter Brook's production of "Sergeant Musgrave's Dance" by John Arden

Gothard with grandfather, Mutford Village, Suffolk

David’s family home where he was raised